Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease

Cranial Cruciate Ligamant Disease

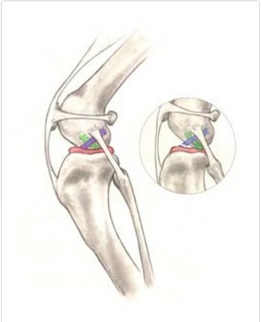

The cranial cruciate ligament (or CCL, see Figure 1.) is one of the most important stabilizers inside the knee. In humans the CCL is called the anterior cruciate ligament (or ACL). The meniscus (Figure 1) is a ‘cartilage-like’ structure that sits in between the femur and the tibia (thigh and shin bones). It serves many important functions in the joint such as shock absorption, position-sensing, and load-bearing and is frequently damaged when the CCL is injured. Traumatic rupture can happen in dogs but it is extremely rare. Most commonly CCLD is caused by a combination of many factors, including aging of the ligament (degeneration), obesity, poor physical condition, conformation and breed. (....read more)

Figure 1. Illustration of the anatomy of the dog’s knee: Blue = cranial cruciate ligament; Red = meniscus; Green = caudal cruciate; the insert shows a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament (also note that the shinbone is displaced forward and is crushing the meniscus)

Signs and Symptoms

You may not notice a severe lameness initially, especially if both knees are affected. One common symptom is that dogs will not sit ‘square’ anymore but rather put their leg(s) out to the side when they sit down.

You may also observe that your dog has:

- Difficulty rising

- Trouble jumping into the car

- Decreased activity level

- Muscle atrophy (decreased muscle mass in the affected leg)

- Decreased range of motion of the knee joint

- A popping noise (which may indicate a meniscal tear)

- Swelling on the inside of the shin bone (fibrosis or scar tissue)

Many dogs will shift their weight away from the damaged leg when they stand but the lameness is less obvious during walking especially with partial tears of the CCL. When a partially damaged ligament ruptures completely or the meniscus becomes damaged your dog may also become non-weight bearing lame and may hop on three legs. This change in lameness may happen suddenly, usually without major trauma (a minor traumatic event may cause the partially torn ligament to rupture completely). Dogs with chronic (late stages) of CCLD usually show symptoms associated with arthritis, such as:

- Decreased activity

- Stiffness

- Unwillingness to play

- Pain

Diagnosis

Diagnosing complete tears of the CCL is easily accomplished by a combination of observation of your pet’s gait, palpation of the knee, and radiographs (x-rays). X-rays are usually taken to: confirm joint effusion (fluid accumulation in the joint which indicates that there is a problem within the joint) evaluate the degree of arthritis aid in surgical planning rule out concurrent disease conditions such as bone cancer

For the TPLO repair specific X-rays are required and hence Dr Davidson may need to repeat radiographs of the knee even if your primary care veterinarian has already taken some.

Specific palpation techniques that veterinarians use to confirm a problem with the CCL are the ‘cranial drawer test’ and the ‘tibial thrust test’. These tests confirm abnormal motion in the knee and hence a rupture of the CCL.

X- rays do NOT show the status (i.e. intact or damaged) of the CCL or the meniscus since those structures cannot be seen on X-rays. It is crucial that the surgeon evaluate both of these structures (meniscus and the cruciate ligament) when performing the selected surgical repair. This is accomplished via an arthrotomy (opening of the joint) and is combined with the surgical stabilization procedure itself since both procedures require full anesthesia and clipping of the animal.

Treatment

Many treatment options are available for CCLD. The first major decision is between surgical treatment and non-surgical (also termed conservative or medical) treatment/management. The best option for your pet depends on many factors such as your pet’s activity level, size, age, and conformation, as well as the degree of knee instability. Pet owners should contact a surgeon as soon as they notice signs and symptoms in order to achieve the best results.

Surgical treatment is generally recommended for CCLD since it is the only way to permanently control the instability in the stifle joint and to evaluate the structures within the joint. Surgery addresses the two major problems seen with CCLD.

- Stifle instability because of loss of the CCL

- Damage to the medial meniscus commonly seen in conjunction with CCLD

Again, meniscal injury will be addressed by your surgeon by removing the damaged parts of the meniscus when performing surgery to stabilize the knee. To address stifle instability many surgical treatment options are available. These different techniques can be categorized into two groups based on different concepts:

Surgical Treatment

To address stifle instability many surgical options are available. These different techniques can be categorized into to two groups based on different concepts: Osteotomy Techniques and Suture Techniques.

1. Osteotomy techniques require a bone cut (osteotomy) which changes the way the quadriceps muscles act on the top of the shin bone (tibial plateau). Stability of the stifle joint is achieved without replacing the CCL itself but rather by changing the biomechanics of the knee joint. This can be accomplished by either rotation the plateau (slope) of the shin bone (Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy - TPLO) or by advancing the attachment of the muscle (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement - TTA). The Osteotomy technique is preferred for large active dogs.

Even though Dr Davidson learned the TTA procedure in 2006 and has mastered this procedure, Dr Davidson is not currently recommending the TTA procedure at this time due to the difficulty and risks of fracture involved in removing the TTA implants should an infection occur. An absorbable TTA implant is currently under development and Dr Davidson will be happy to offer the TTA procedure again once that technology is fully developed.

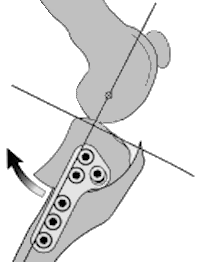

Figure 2. Illustration of the concept of the TPLO procedure

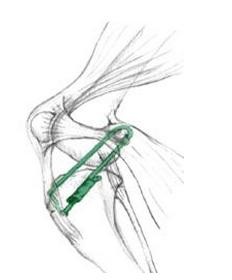

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) involves making a circular cut in the tibial plateau and rotating the contact surface of this bone until it attains a relatively level orientation that puts it at approximately 90 degrees to the attachment of the quadriceps muscles (Figure 2). This orientation of the tibial plateau renders the knee relatively stable, independent of the CCL. The cut in the bone needs to be stabilized by the use of a bridging bone plate and screws (Figure 3). Once the bone has healed, the bone plate and screws are not needed, but are seldom removed unless there is an associated problem. The greatest advantage of this technique is the perceived superior outcome (limb function and less progression of arthritis) compared to traditional suture techniques especially in young, large breed dogs. Dr. Davidson earned her TPLO certification in 2000 and has performed in excess of 1500 of these surgeries over the last 15 years. In other words, Dr. Davidson probably has more experience with the TPLO than any other surgeon in the Dallas Fort Worth Metroplex.

Suture techniques can be divided into intra- articular (within the joint) and extra-articular (outside the joint) procedures. In humans intra- articular replacement of the ACL using some form of ACL replacement is the most common procedure. This approach has been studied extensively in dogs and found not to be successful mainly because of the difference in anatomy and underlying disease process. Many companies and surgeons are revisiting this possibility utilizing novel developments. Because of the disappointment with intra-articular techniques to date, suture techniques are currently performed in an extra-articular fashion in dogs.

The most commonly performed technique is called extra-capsular suture stabilization and utilizes strong suture material that is placed just on the outside of the knee joint (but under the skin) to mimic the CCL and stabilize the joint. A variation of this technique is called Tightrope® and allows the surgeons to use bone tunnels and toggles.

The most commonly performed technique is called extra-capsular suture stabilization and utilizes strong suture material that is placed just on the outside of the knee joint (but under the skin) to mimic the CCL and stabilize the joint. A variation of this technique is called Tightrope® and allows the surgeons to use bone tunnels and toggles.

a. Extra-capsular suture stabilization (Figure 3)(also called “Ex-Cap suture”, “lateral fabellar suturestabilization” and the “fishing line technique”) has been performed for many years. While there are many variations of this technique (different suture materials, ways to tie the suture, how to attach the suture to the bone and so forth), the general concept of this procedure is to replace the function of a defective CCL on the outside of the joint. This is usually accomplished by utilizing a strong suture placed along a similar orientation to the original cruciate ligament. The suture needs to stabilize the knee joint, while allowing normal knee movement, until organized scar tissue can form and assume the stabilizing role.

The most common complications after this procedure involve failure of the suture and progressive development of arthritis. Suture failure tends to be more common in larger, active dogs; hence many surgeons reserve this technique for small breeds, older, and/or inactive dogs. The main advantages of this technique include the lower cost and the lack of a bone cut.

Postoperative care

Postoperative care at home is critical. Premature, uncontrolled or excessive activity, risks complete or partial failure of the surgical repair. When choosing a suture repair, this failure may simply mean that the surgery has to be performed again but when choosing an osteotomy technique this failure may mean that a much more invasive approach is now needed. Proper postoperative care limits activity to leash walking for a minimum of 8 weeks and no running, jumping, rough-housing, or off-leash activity. While it is important to control activity it is also important to maintain muscle mass and joint function (range of motion).

Studies show that physical therapy can speed the recovery and improve final outcome regardless of the chosen surgical technique. This rehabilitation should start immediately after surgery and usually includes a regime of passive range of motion, balance exercises, controlled walks on leash and so forth. Discuss details with your board-certified surgeon and/or primary care veterinarian.

The long term prognosis for animals undergoing surgical repair of CCLD is good, with clinical reports of improvement in 85-90% of the cases. Unfortunately, arthritis progresses regardless of treatment, however much slower when surgery is performed. Therefore, medical arthritis management/prevention is recommended for any dog with CCLD regardless of the chosen surgical. It is important to realize that arthritis is a progressive disease and develops fairly quickly in an injured (or damaged) stifle joint.

The most common complication caused by CCLD is long-term impairment due to arthritis. Other complications associated with arthritis and CCLD include loss of range of motion in the joint, muscle atrophy, and loss of full function of the limb, as well as decreased activity. Unfortunately, neither human nor veterinary surgeons are able to completely restore normal joint anatomy and function. Even with surgery some progression of arthritis is expected. It is important to understand that arthritis is an irreversible disease and hence everything should be done to prevent its development or progression. Therefore, two steps are crucial when treating CCLD:

1. surgical repair and

2. medical management of arthritis

The second most common complication caused by CCLD is tearing of the meniscus. Due to the instability in the knee joint, the inside (medial) meniscus frequently gets damaged. This can happen during the initial injury or even later after surgical repair of the CCL. Meniscal damage in dogs is addressed by removing the damaged parts of the meniscus since it is too small to repair. A meniscal tear is very painful and if a damaged meniscus is left in place the animal will not regain full function. Removal of the damaged parts of the meniscus (if present) will be performed by Dr Davidson during the chosen procedure to address the knee instability. If Dr. Davidson finds that the meniscus is not torn she will preform a meniscal release which is a small transverse cut in the back portion of the medial meniscus that will usually prevent meniscal tearing and damage after surgery.